This morning, the sun rose on a beautiful September day – intense blue skies, crisp air, birds singing their last few songs before heading south. Trying to start the day on a calmer and more positive note than the day before, I took my early morning cup of tea and a blanket and curled up on my favorite chair on the porch. Lifting my face to the warm sun, I closed my eyes and took a deep breath of the cool, fresh air......and smelled the lingering and noxious fumes of the paint I’d used on the metal basement door twenty feet away, my last chore of the busy day before. No matter how beautiful the day appeared, there was no escaping the ever present unavoidable reality of that odor. Somehow, it all seemed like a metaphor for my life these days. I can’t escape the fact that underneath the calm of any particular moment lurks the very real evidence that all is not well. Whereas I can be assured that those smelly Rustoleum fumes will fade away, that kind of assurance only applies to things like paint odor, head colds, and traffic jams. I am all too aware that there is no assurance that things will get better in one of the most terrifying things in my life, the worsening of the crisis in the DSP workforce, those hard-working, caring people without which my daughter cannot survive. Yesterday was a demanding and depressing day. I spent most of three hours participating on the phone in meetings on the DSP Workforce Crisis. I couldn’t attend in person because I was providing care to both my husband and daughter at the same time as these meetings. (Read Sandwiched: Caring for an Adult with Developmental Disabilities and an Aging Spouse) These meetings are too important to miss, so I conferenced in so that I could listen and interact with professionals, advocates, parents, and DSPs trying to find a way to deal with this worsening crisis, and our inability to engage policymakers and purse-string holders in understanding the problems in the DSP workforce. The DSP workforce is as vital to most individuals with developmental disabilities as oxygen. Despite rhetoric about choice and control, individual rights and inclusive, community-based supports, the quality of support is decreasing; the instability of supports is increasing. How can it not? Staffing ratios are down, turnover is high, vacancies can’t be filled, DSPs are working multiple shifts and multiple jobs. All of this is occurring in systems overburdened with rules and regulations and underfunded in general. Parents with children in provider care note incidents occurring because the revolving door of DSPs doesn’t know their child’s needs or are unfamiliar with behaviors. Parents whose children are self-directing can’t find DSPs. Parents don’t know if their child will have care from one day to the next. They’re quitting jobs and incurring financial hardships in order to care for adult children. Aging parents have no choice but to bring adult children home for weekends from group homes and supported apartments because the provider can’t provide staffing. There are reports of individuals going missing and perishing not because of their own challenges but because of inadequate staffing. Increasingly complex systems requirements mean that DSPs in already understaffed supports are spending too much time on paperwork and not providing necessary supports and oversight. Providers struggle with overtime and the costs of turnover. These things are happening today while we are still here to advocate for our children, help them deal with issues, provide their care, but we are getting older, and we are struggling now.....who will provide stable, adequate care tomorrow?.....I don’t mean our future tomorrows, I mean the next morning that the sun rises in the lives of our children. It seems like I’ve been moaning and complaining about this issue forever. I’m even tired of listening to myself. But the problem is so excruciatingly important, so desperately real that its looming presence lurks evilly through every minute of every day. I find myself launching into soliloquies in front of total strangers searching for just the right words to adequately and succinctly represent how important this issue is, the impact it has on individuals, on families, on providers who strive to create quality supports despite many roadblocks. I’m worried that people aren’t really listening......especially those that can make a difference. We’ve said it all before; they’ve heard it all before. Are our words becoming like static, white noise, to which they no longer pay attention? I want to scream, but nothing has changed! nothing is getting better! In the last five years—since we started seriously advocating on this issue—we have had some funding increases for DSPs. What amounts to about a dollar an hour total increase in DSP pay rates is helpful, but leaves pay rates still far less than commensurate with the skill and responsibility required for the job, and has been insufficient to affect vacancy and turnover rates. At the same time the cost of living has increased, rising about five percent in the last few years with the biggest jump in 2018 of 2.8 percent, shrinking the value of that dollar increase. And the minimum wage in New Jersey will have increased by over two dollars an hour by January 1, bringing it ever closer to the average pay rate of a DSP in New Jersey. A Direct Support Professional does not do minimum wage work. This crisis is costing lives, it is endangering well being, it is impacting the ability of individuals with developmental disabilities to live lives of value and dignity and it is robbing parents of any hope that their children can live acceptable lives after they’re gone. It is also depleting the historically underfunded resources available for supports for individuals with developmental disabilities. The President’s Committee for People with Intellectual Disabilities estimated in 2018 that there were 1,276,000 DSPs in this country. They estimate that is costs $4,073 to replace a DSP. With turnover rates at about 45% that means that 574,200 DSPs had to be replaced in 2018 at a cost of $2,338,716,600. Increasing pay rates is the critical first step in addressing the DSP workforce crisis—a reasonable pay rate will attract workers and offer them more than the near poverty level wages they receive now. DSPs are simply not being recognized for the valuable, difficult, interdisciplinary work that they do and the skill and training that it requires. In order for DSPs to be valued, the developmentally disabled population has to matter......to more than their families and the people who work in the DD community. The DD population is the most underrepresented, undervalued, under respected segment of our population. Is it any wonder that the people who provide critical supports for them are undervalued as well? Before this day is through, I have to put a second coat of paint on that door.....which means those paint fumes will linger into tomorrow and what is supposed to be another beautiful morning in this string of beautiful fall days we’re having. I think I’ll find another spot to drink my tea. I don’t need a reminder that a new day has dawned and all is definitely not well.

0 Comments

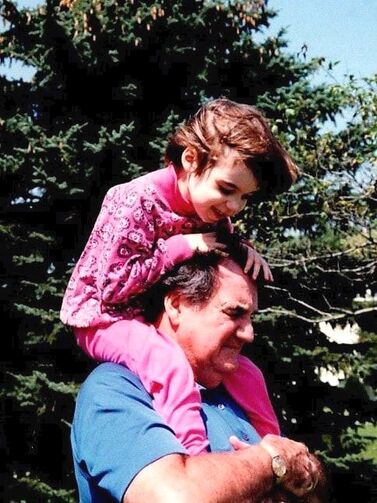

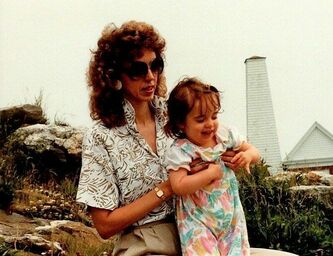

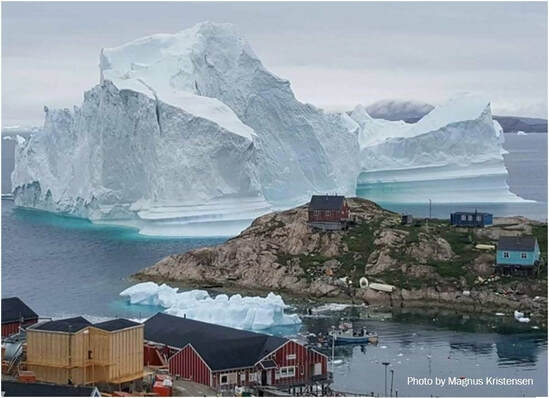

My last post, reflected on the Father’s Day fears of my husband, an aging father of an adult daughter with severe disabilities. Just five days after it was published, our family experience moved past fear and moved closer to the reality of our future. In an instant, George’s abilities, my responsibilities, and our combined ability to dedicate time to caring for Lauren changed. While visiting with Lauren, my husband fell fracturing his right hip. Five days of hospitalization an hour away from home, hip replacement surgery, and two weeks in rehab ensued. At eighty three, with other complicating health conditions his recovery is slow. Seven weeks post surgery, he is still walking with a walker, needs help with much of his personal care, and I drive him to physical therapy and doctors appointments three or four times a week. We don’t know how many of his prior abilities he will regain. Will he be able to drive again? (It’s his right hip) How much of his general mobility and skills will remain impaired? Those are important questions for him and for me. I can’t leave him alone right now for more than a few hours. He drops his phone He spills a glass of water. He needs me for a myriad of reasons. But Lauren needs me too. A couple of weeks ago her seizures suddenly started escalating—longer and stronger. It’s the first hint of instability in her seizure pattern in many years. I admit—I went into panic mode. We lost our neurologist of thirty years a year ago when he suddenly stopped seeing adult patients. Now we have a new neurologist who does not have the experience of partnering with parents to literally keep children alive through the tumultuous years of childhood seizures. The former doctor and I weathered the medication changes, adjustments, combinations, and now a new doctor seems totally unfamiliar with the trauma and trials of those years......and all it taught us. So, I am scared that this new doctor is untried, untested compared with our old one. And, I am scared that if a significant seizure issue develops, Lauren will have to be hospitalized. What on earth would I do then? I would need to be in the hospital (also an hour away from home) with Lauren. But I cannot leave George alone. Sure, we have family and friends, but no one in a position to step in to help at this intensive level. People have jobs and their own responsibilities. I can’t depend on Lauren’s DSPs helping because they would not be paid under Medicaid rules. The State budget that pays for Lauren’s DSPs is Medicaid dollars. Her hospital care would be paid by Medicaid. They do not pay for both at the same time. It’s a huge issue for many individuals who are hospitalized and need the continuing care of experienced, familiar caregivers. It’s something that is a serious worry for Lauren’s future when I am no longer here. If you’ve experienced any loved one being hospitalized, you know that a constant advocate needs to be present during that hospitalization. While George was hospitalized, he could answer questions, ask for help, yet I still needed to be there to deal with constant medication errors and issues with care for him at a highly-rated hospital. How can someone like Lauren— non-verbal, cognitive disabilities, unable to feed herself or participate in her own care—survive a hospitalization? When this question was posed to the head of the state division serving those with developmental disabilities, his response was that the hospitals would just have to train their people better. The response is obtuse, incredibly naive, dangerous, and downright cold. We have adjusted Lauren’s seizure meds and.....so far, so good. But now a new worry has surfaced. One of Lauren’s DSPs is having a knee replacement and will be out for three months. We’re in the middle of an escalating DSP workforce crisis across the country, and we lost our sub a few months ago. Will we be able to weather this vacancy without the need for me to cover shifts? I can’t be in two places at once. Needless to say it’s been a stressful last two months. I haven’t published a new post since this all happened because there simply has been no time to write. My life is consumed with George’s, and Lauren’s, needs. I struggle to be everything I need to be for them both. I frequently write about fears and worries for the future. Now I find the present is that future I so feared......and rightly so. My focus of many years has had to shift. My attention cannot be as much on building an acceptable future for Lauren as surviving the present. I am just fiercely treading water. So far, I’ve been able to meet everyone’s needs. George is recuperating. Lauren is stable again. There are no vacancies in staffing for at least two weeks. In essence, no one is drowning.....today. I’m just hoping that I’m not put in the position of having to choose between which one of them I reach out to save.  The first greeting card that I picked up in the pharmacy showed a little girl dancing with her father, her small feet in red Mary Janes perched on his own. Adorable card? Yes, but totally inappropriate. I was getting frustrated. This was the third store I had visited in my search for a card for my daughter to give her father for Father’s Day. Card after card had unsuitable illustrations on the front, and inside, verses referring to the things that a Dad teaches a daughter, the journey to adulthood and independence, the shared adventures.....none of which were something Lauren could give her father. None of them reflected my non-verbal, non-ambulatory daughter’s experience of being raised by her father, because at thirty-three, Lauren is still much like a very young child, but in an adult body. She and her father have not shared slow dances or fast balls, learning to drive or celebrating a coveted new job. How do you find the card that reflects the fact that this father’s daughter still needs the level of care that she did over thirty years ago, and that he, at eighty-three, is no longer physically capable of providing that care? How do you find a card that does not simply provide a sad reminder of what hasn’t been, what they have not shared, and his fears for her future? Those fears are something he lives with every day. Although I am the one dealing with hiring, training, and managing the DSPs that provide Lauren’s care, her father watches from the sidelines. He absorbs my frustration and concerns about the growing crisis in the DSP workforce. He knows that we live on a knife edge of stability, the loss of one DSP will plunge Lauren into vacant shifts and uncertain care which could take months—or longer—to stabilize. He knows that if something should happen to him, I will do what I can to help Lauren weather the uncertainty of minutes and hours with inadequate or unavailable care. He also knows that if something happens to me, he does not have the ability to do the same. Aging has robbed him of the capacity to function as he once did, but has not diminished the worry and doubt about the present and future well being of his much-loved daughter. No matter how we plan or how hard we try, we cannot assure Lauren’s continued well being and safety as long as the DSP workforce crisis rages on unabated. I cannot assure my daughter’s father that tomorrow, and all of the tomorrows he will not be here to watch over her, will find her safe in the care of someone who is ready and able to meet her needs. This is the child who just moments after her birth stopped crying when she heard his voice. This is the child that will watch football with him – unable to see the screen or understand the game – because he is sitting next to her. This is the child he held through seizures, illnesses, and too many doctor’s visits to count. This is the child, now a woman, he must leave to someone else to care for beyond his days. There are many fathers out there this Father’s Day weekend who are worrying about the well being of their sons and daughters with developmental disabilities, worried because we do not have a workforce adequate in number to provide their care. Parents have shared their stories; have shared their very real concerns. Advocates have spoken up, and showed up, to underscore the need for action. Legislators have listened to our pleas and pledged their support. And yet, there is resistance from critical people who stand in the way of the state investment needed to begin to address this crisis. I hope when those people celebrate with their own healthy, safe children this weekend, they take a moment to realize that disability does not discriminate. It arrives without warning or consideration of wealth, status, or capability. The typical life journey of their children is as much a matter of chance as the atypical and challenged journey of ours. I hope they will be thankful. I hope that in the weeks to come, they will look beyond politics and parties and simply do the right thing. In the meantime, I will continue my search for a card that will allow Lauren to wish her devoted father a simple and sincere "Happy Father's Day!", on a day when he can still celebrate that his no-longer-little girl is still safe and cared for the way he hopes she always will be. Mother’s Day Reflections from the Mother of an Adult with Severe Developmental Disabilities5/8/2019  “Happy Mother’s Day!” I first said those words as a very small child prompted by my father, not really understanding the significance of being a mother other than knowing I had one. Over the next fifty-three years or so, I said those words to my mother each year, sometimes in person and others on the phone when distance separated us—until death separated us. I’ve also said those words to family members, friends, and even acquaintances, most have responded in kind little knowing the little jolt I feel when those words are directed toward me....because the one person that I’ve never heard those words from before is my own daughter. Because of her severe developmental disabilities, at thirty-three, Lauren is like the small child I once was who did not yet understand the concept of motherhood. Her Dad buys the prerequisite card and gift, signs her name to the card, tells her what she’s giving Mom for Mother’s Day, and speaks for Lauren while presenting her gift. How much of this little family play she understands, I do not know. I think she understands that I am “Mom”, but her understanding of parenthood and the responsibilities of motherhood is questionable. To say that she understands that I am her mother is, perhaps, what I want to be true more than what actually is. Without understanding the concept of motherhood, how can she grasp that being “Mom” is more than just a name she should know me by? She simply knows that I am the one permanent female fixture in her life. She knows that I have been with her for all of the bad moments of her life and I have been by her side for too few good ones. She probably does not know that Mom is not just my name; it is my role in her life. When Lauren was younger, it bothered me to know that I would never hear my child call me Mom. But I realize now that it was not just the spoken word for which I yearned. I needed her to know what a mother was and comprehend all of the love and sacrifice and fierceness that entailed. Perhaps I wanted her to be reassured that I, beyond anyone else, would always be there to ease her difficult journey through life. But I think I also needed her to understand that this is a two-way relationship, as if that understanding could fill the emptiness of never seeing my child’s arms reach out for me or of hearing “I love you” from her sweet pink lips. Lauren has no concept of the work or the determination it has taken to get us through the last thirty-three years. So many of those years have been a blur of frustration and exhaustion endured while trying to meet Lauren’s needs in a world that all too often seemed to say no before a request was even made, a world that said not here, not now, not ever. There wasn’t a lot of time for deep dives into perspective and reflection. But with Lauren living in her own home now, I have a little more time, a little more distance from the minute to minute reminders of her complete dependence on my love and support in her life. I’m sure it’s also my age that is prompting more reflection. It’s time to look back at where I’ve been, who I’ve been, and what can still lie ahead. One thing is glaringly obvious to me at this point; I have not been the mother I had planned to be. I think if Lauren had been a typical child, I would have only skated across the possibilities of all that a mother can be. I would have been too focused on achievements and the opportunity to bask in the reflected glow of my child’s accomplishments—as if they were the measure of my success in mothering that child. But Lauren is not a typical child and the mother I have had to be has had to learn more than teach, love more than been loved, and admit that in the recesses of her heart—those places we must be forced to go—lay the meaning, the truth, and the wisdom of motherhood. On Mother’s Day, I will be the one to go to Lauren and reach out to wrap my arms around her. I will look for clues that she feels connection in the expression on her face, the tilt of her head, or within the passing grace of her shy gaze. I know that I will feel our connection. I will feel the unbreakable ties binding us to each other. I will feel a depth of love for this child that I may never have known was possible without her in my life. It is her real gift to me for all of the Mother’s Days in our life together. Being a mother....having a mother—two vastly different states of being that have determined the course of my life. Where once I said the words “Happy Mother’s Day” to my mother, now I say those words for my daughter, because she cannot say them herself, and I would do anything for her. And also because those words do not just celebrate me, they celebrate us and all we have both managed to become while I have held her within the circle of my love.  It’s been so lovely lately to wake each morning to the softer breezes of spring days and the brilliant green of budding trees, but unfortunately spring also brings a flurry of paperwork related to Lauren’s continuing ability to live an adult life. In the last week, I’ve been complaining to all who would listen about complicated forms without adequate instructions, the amount of time it takes to gather all of the necessary info every year, and the need to once again prove that Lauren is indeed still disabled. Oh yes, the only miracles occurring here will be if my tulips survive the hungry deer. It is essential that the paperwork necessary to maintain the multiple resources that I coordinate in order for Lauren to live life as an adult be completed. But the time and effort it takes to repeat this process every year seems kind of ridiculous. Nothing substantial changes on the forms, reapplications, and assorted paperwork that I need to submit and—since we are not expecting any miracles—it probably never will. But yet that paperwork must be completed each year requiring submitting multiple forms and supporting documentation to multiple agencies, all with their own set of rules. But as I complain, I feel guilty because, in truth, I should be incredibly grateful. One, because these resources—cumbersome though they may be—are available, and two, because they enable Lauren to spend her days happily and safely in a life that fits her needs and preferences. My need for gratitude has been made very clear to me by the conversations I’ve had in the last few weeks with parents and DSP’s who have related stories of truly unacceptable levels of care that individuals are receiving. My need for gratitude is also prompted by the news reports that continually pop up on my computer screen making my issues with Lauren’s supports pale in comparison with the quality of the supports of others. So, I feel guilty that I have been complaining, because although Lauren’s life is difficult to manage and tenuous in its long term stability, she is safe and secure right now. Right this minute, I know that Lauren is receiving good care in a clean, pleasant home that addresses her physical needs, provides options for her favorite activities and interests, and holds her treasures and photos of family and friends. Right this minute, I am as comfortable with the quality of Lauren’s life as this worrywart of a mother can be. I remain concerned about the future, about finding DSPs in a workforce crisis to continue to provide the quality of care that Lauren needs. I worry about a constantly changing system of supports, and services based primarily on the consistently threatened funding resource of Medicaid. And, how can I not worry—since Lauren’s supports are a complicated and delicate balance of multiple resources—about who will oversee Lauren’s life and manage all of this paperwork when I can no longer do it. But I do not fear for her safety and well being today. Too many other parents cannot say that about their child. Several recent news reports about the supports, or lack of them, provided to individuals with developmental disabilities across the country have been terrible enough to remind me of the expose of Willowbrook reported forty-seven years ago. And just like the excruciatingly slow response to the horrors uncovered in that institution, little is changing in any substantial way for the individuals experiencing inhumane conditions today. In 2016, the Chicago Tribune printed a three part series about the unchecked, unaddressed incidents of abuse and neglect within the Illinois system. In February of this year, the Tribune followed up reporting, “Despite Illinois’ promise to reform troubled group homes for disabled adults, allegations of abuse and neglect have risen, staffing levels have fallen and state oversight has been sluggish...” The Tribune also reported that admissions to institutions have increased despite Human Services administrator’s intent to close those facilities based on the reasoning that “state centers were an antiquated luxury”. I would love to understand their definition of “luxury” and whether anyone living there would describe it using the same words, especially since some of the residents that were moved to group homes were “near death from disease... victims of suspected sexual assault or suffered unexplained injuries”. Here in New Jersey, a few providers have been under scrutiny for substantiated claims of abuse and neglect. and one particular one was in the news again last month despite the fact that a national monitor was brought in last year to review safety and quality of care issues in that organization. The monitor’s report, completed on February 1, has not been released to the public. And, apparently, the issues are still occurring. There are genuinely good providers out there, providing wonderful supports to an extremely diverse population. They are creative, flexible, and doing the best they can with inadequate funding levels and a crisis in the DSP workforce. But there are evidently not enough good ones out there because there are still too many despondent parents struggling to find better care for their children. And distressingly, there are too many parents who feel unable to speak out about inadequate care, because they fear their children will experience retribution and worsening care. In conversations with parents and DSPs in the last few weeks they’ve told me about individuals not being bathed or shaved, spending hours in wet and soiled diapers, being dressed in inadequate clothing or even without underwear. They’ve related unexplained injuries, empty refrigerators in group homes, and over medication or doctor’s orders not followed. And others have experienced days spent in emergency rooms waiting for some provider or some facility willing to provide care. So I feel guilty complaining about what I must do to sustain Lauren’s adult life, and for often being swamped with worry about the unknowns Lauren faces in the future. Too many individuals are suffering today. We parents of children who are well supported and leading decent adult lives must not be complacent, because until all individuals with developmental disabilities are safe, none of our children with developmental disabilities are safe. Until there are consistent outcomes of respectful, safe, and well run options for adult living for all individuals, all of our children are vulnerable. Their living situation could deteriorate because of a change in the system, a change in their needs, or a change in their circumstances. There are no guarantees. And complacency—because today your child is just fine—is a dangerous thing. All parents should be able to know that no matter what, decency and accountability inform the bottom line of service provision of any organization providing supports for their child. It should not just be the good fortune of some. I hope that those of us who can enjoy these spring mornings, because we’ve had a restful night knowing our child is safe and well cared for, will add our voices to those of parents who cannot rest. They need our support. I hope we never need theirs.  When my daughter was younger, I had this notion that parents who had adult children with developmental disabilities living in a group home or other setting had crossed some kind of finish line, as if their intensive effort of many long years had resulted in success. They were able to safely hand off the day-to-day support of their children to others who were unimpeded by aging bodies and exhausted minds. Perhaps for some parents, this is true. But I don’t think it is for most of the parents of children with severe developmental disabilities that I know. It definitely isn’t for me. I’m afraid that there may be no such thing as a finish line, or a time that making sure that Lauren’s intense and diverse needs are met, won’t be primarily up to me. When people I haven’t seen for awhile inquire about my daughter, I say, “Lauren’s doing well! She’s living on her own now.” Of course, then I have to explain that “living on her own” means that someone is with Lauren 24/7 to support and care for her. I usually don’t include the other fact that “living on her own” requires my constant oversight and management of every facet of her life. Lauren may no longer live under the same roof as I, but she still depends on my constant presence in her life. Since Lauren has a severe intellectual disability, as well as severe physical disabilities, she depends on someone to know her well enough and care about her enough to make decisions, guide her choices, and protect her health and well being. That would be me. Eight years ago when I was making this adult living concept a reality for Lauren (her own rented home with 24/7 staffing), I mistakenly believed that this distance between us—her in one house, me in another—would also create space between the worries and anxiety that were a constant presence when she was home. It has not. I still worry about all of the same things, plus now I feel constantly in a no man’s land in the war between my need to support her in an independent adult life, and my need to have her within easy reach and under my watchful eye. Sometimes I think it would be less stressful to just bring her back home, eliminate our “separateness”. Then I would be able to monitor every moment of her life. I would be able to touch her, to look into her eyes, to ponder the subtle intonations of her vocalizations. But I cannot give in to that because it would be selfish. Lauren does not live in a home of her own because I do not want her living in mine. No, Lauren lives in a home of her own because she needs to build an adult life in which she can survive without me. This arrangement is the first step. It’s not perfect because I am still so heavily involved in her life, providing support I won’t be here forever to provide. But this is a good first step, because while I’m still involved in the days of her life, I am not involved in the minutes. Those minutes are under the watchful care and support of the wonderful Direct Support Professionals (DSPs) that Lauren has in her life. They know her well and provide consistent and diligent care, but no DSP will ever know her as well as I do. She may have five other people facilitating those moments in her days, but I have the final responsibility of figuring out if a question or concern is “something” or nothing. A vocalization could mean anything from I’m in pain to I don’t like that song. A pale face could mean I don’t feel well, I’m tired, or It’s too warm in here. A refusal to eat could mean I’m feeling nauseous, I don’t like that sandwich, or I want the television on. The possibilities of Lauren’s subtle cues are endless. When a DSP can’t figure out what’s going on with Lauren, it’s up to me to figure it out.....or to make an educated guess. Lauren’s care places a lot of responsibility on the shoulders of the DSPs, but I still hold most of the clues to the messages hidden in Lauren's wordless existence. And so, though even I am not always right, the final judgment on everything rests with me. Lauren recently had a little cough. It wasn’t getting better. But, it wasn’t getting worse either....until suddenly, on a Sunday of course....it started to sound different. I jumped in the car at eight o’clock at night, because in speaking to two different DSPs who had just changed shifts, I was getting two differing reports on Lauren’s condition. Lauren was definitely worse, but call-the-doctor-in-the-morning worse not a rush-to-the-ER worse. I ended up staying through the night to monitor her, to try to make her comfortable while the cough was interrupting her sleep. Lauren doesn’t get sick all that often. Her DSPs just don’t have as much experience as I do with helping her weather an illness. Lauren’s doctor—who sees her for maybe fifteen minutes a couple of times a year—does not know Lauren well enough to “read” her in anyway. And, whether the doctor is saying, “Take a deep breath” or “Open your mouth”, I have to explain that Lauren doesn’t understand her instructions and help her get the result she needs. Since the doctor is looking at an individual who is so atypical of the majority of her patients, it’s up to me to decipher for her what is typically atypical for Lauren and what is not. And, since Lauren cannot tell us what she is feeling, it’s up to me to guess and relate that to the doctor. She must then consider my input with her exam, made with the limited cooperation of Lauren, in order to come up with a diagnosis. It’s not the ideal scenario. The doctor prescribed an antibiotic for an upper respiratory infection and an antihistamine to control the mucous. The antihistamine allowed Lauren to have the first decent night’s sleep in awhile, but left her too groggy to eat the next day which she primarily slept through. The antihistamine had to be discontinued. I’m hoping the antibiotic kicks in soon, because she’s still not herself and I can’t stop worrying that I’m missing something until she is. So while we wait for this wonder of modern medicine to hopefully start working, I’m on the phone, talking and texting, with the DSPs, issuing instructions, and trying to walk the fine line between trusting those very able DSPs to care for Lauren and wanting to do it myself. Yesterday, when I stopped in and sat for an hour next to a clearly fatigued and pale Lauren, the DSP said to me, “You really have to stop staring at her.” And, she was right. I was unnecessarily focused on Lauren’s thin form as if some nuance of her breathing or the distinct shade of her pale cheek held some critical message I couldn’t miss. I need to give her the time she needs to rest and recuperate, but I can’t stop worrying that she’s actually not getting better......and I’m not seeing it. I talk about that hypervigilance in my recent post on PTSD in parents of children with developmental disabilities. There are no days that I do not wait for the phone to ring or wonder why the phone hasn’t rung. It’s just the reality of this arrangement. I am in charge of guiding Lauren’s experience of life, her ability to travel safely through her days. Normally, I physically visit her two or three times a week. There are often times when I feel that she doesn’t seem quite right, but I can’t figure out why. So I dwell on it for the rest of the day weighing possibilities, fearing possibilities....until I can check on her again. Hopefully, I find out that she was fine after I left. What she needed was for me to leave. Sometime she makes that quite clear by pushing me away when I lean down to plant a smooch on her cheek. I’m interrupting her day. Thankfully, there are other days when all is well, and I sit on her couch with her as she leans into me resting her head against mine. It’s a “mom moment” I live for and the sun shines the rest of the day, regardless of the actual weather. I can’t believe it’s been almost eight years that Lauren has been on her own. I expected it would get easier, more mundane at some point. It has not. Lauren really loves this life on her own. She doesn’t even want to come home to visit anymore. It’s as if my home is a “been there, done that” place in her life that she doesn’t need to revisit. It kind of hurts. But I’m also really proud of her. This bit of independence shows a maturity of which I didn’t think she was capable. But, there is always something tearing at the fragile web of stability that is Lauren’s life. If it is not a problem directly with Lauren, it’s a problem with staffing, funding, new rules, or old equipment. Lauren’s well being is not just dependent on her physical care, I am also responsible for making all of the ancillary details of Lauren living on her own coordinate to support her life – finances, staffing, housing, transportation, etc. So when I share my news with people and they react with “Oh, that’s great!” I agree, at least in theory. I don’t think they can understand the investment of my time and knowledge that it takes for Lauren to successfully live on her own. I don’t think they will grasp how very mixed my emotions are about this situation. As I wrote in Special Needs, “....I feel selfish that I am not with her every moment to ease her way through this challenged life that I have given her. Is it my responsibility to prepare her to live without me? Or, is it my responsibility to dedicate my every waking, and sleeping, moment to personally assuring her comfort and safety? Somehow, it’s both and that’s impossible. I know that. And still, I feel guilty.” So I have loosened my grasp on the minutes of Lauren’s life, but as of yet, there is no one who can be “me” when I have ceased to be, and there is no entity within the system of supports prepared or designated to become me when needed. This finish line that I thought was something that parents reached is in reality something their children reach—the ability to live independently of their parents. It’s a finish line that Lauren depends on me to help her reach, and that is definitely an added worry, because I don’t see it anywhere on our horizon. Isn’t it Sad....That We Need to Compel Others to Care about Adults with Developmental Disabilities?3/20/2019  In Special Needs, I wrote about some of the comments that my daughter and I frequently get from community members who encounter us during the course of their day. In between the “I’m so sorry for you.” and the fervent “God bless you” responses, there are the sad but furtive glances steered our way. People mean well. They think they understand, but really, they don't. They do not realize that although Lauren’s life is severely challenged and our life together is far from easy, the saddest part of our journey is actually the challenges and roadblocks added by the world around us to the challenges with which Lauren was born: the hurdles of finding, keeping, and managing necessary supports and services, the difficulties in finding providers—medical and otherwise—who can and will address needs, and the indifference, ignorance, and community barriers we all too often encounter. Because my life, by necessity, has become so embroiled in everything “disability”, I sometimes forget that the majority of people have no idea what life is like within the developmental disability community. They are truly surprised that you can’t just ask for what you need in order to obtain it. They also believe that when our children want or need to live somewhere other than the family home, options are easily and readily available. Sometimes I don’t think they believe me when I explain that our communities are not prepared to care for individuals with developmental disabilities. They don’t realize that homes, activities, jobs, medical care, and people to provide the care we parents cannot continue to provide for a lifetime, are significantly lacking. Disability-rights activist Karin Hitselberger recently wrote, "Disability means having to figure out every day how to function in a world that consistently forgets you." Strangers, and sometimes family members, often approach me as if Lauren is a tragedy that has occurred in my life. They speak of reverence of our journey and express that they could never endure the parenting journey I am on. I can understand their fear. I can understand that their inexperience renders them unknowing, not uncaring. What I don’t understand are the people who should know better, yet do not feel compelled to care. I find that incredibly sad. It is sad that the New Jersey Assembly has recently felt it necessary to approve a proposal for a bill of rights for families of individuals with developmental disabilities. The bill seems to be directed at how state agencies, tasked with providing services and supports, treat family members of individuals. I find it very distressing that this issue was deemed such a significant need by the legislature that they took this step to assure that state agencies operate with civility, truth, and compassion toward vulnerable individuals and their families. As Assemblywoman Downey said, “Some of these are things that should be common sense.” A few of the rights outlined in the bill are: The right to be treated with consideration and respect The right to receive return phone calls within a reasonable time frame The right to be given understandable and honest information The right to be free from retaliation if a complaint is made Isn’t it sad that these things had to be spelled out as requirements? A press release stated that the bill of rights will be distributed by the Division of Developmental Disabilities to case managers and “...posted in a conspicuous place in each office of the Divisions of Developmental Disabilities and Disability Services in the Department of Human Services, in each State developmental center, and in adult group homes overseen by the DDD.” But, there are no details about who will judge whether these rights are respected or not. There are no details about what the repercussions will be if they aren’t? Will this bill of rights be “posted” on walls where it will become faded and forgotten—like old wallpaper no one notices anymore? Something else that should be a right—dental care—has long been a struggle to find for individuals with developmental disabilities. Most dentists will not see these individuals. Recently, I read the headline, “Dentists no Longer Permitted to Turn Away Patients with Disabilities” and reacted with Wow, that’s great!. And then I stopped myself. How could this have been permitted in the first place? Why has it taken this long for the American Dental Association to compel dentists to care about the dental health of individuals with developmental disabilities? Within the article it noted that dentists were concerned about the amount of time it would take to treat people with intellectual and developmental disabilities. Jane Koppelman, a senior manager of the dental access campaign for the Pew Charitable Trusts stated, “Sometimes it’s difficult to have a patient in the chair if they are very, very anxious about being treated, if they have difficulty sitting still or if they feel a lot of fear, and sometimes those circumstances are more prevalent in people with varying disabilities.” This seems to imply that it is the dentist that deserves our sympathies....not the frightened patient. I think the individual in pain or discomfort because no one will care for their teeth is the person who deserves our sympathies. How has the dentist been prepared to treat all members of his community not just the easy ones? How have dental schools prepared their students to deal with physical, cognitive, sensory, and behavioral issues? A mother looking for dental care for her child with autism asked in an online health forum if it was legal for one dentist after another to deny her son care. A dentist responded, “...the dental profession and its educational system as a whole have been grossly negligent in producing doctors who are able to treat such patients. ...the dental profession....is just not geared toward accessibility for disabled patients simply because the majority of dental professionals just don't think the effort it takes to treat them is worthwhile.” Wow. Isn’t that sad? I experienced this refusal to treat with my daughter many years ago. Our family dentist wouldn’t see my tiny four-year-old because she had disabilities. Fortunately, I was able to find a wonderful dentist – an hour away – who treated her for many years. That dentist has now retired and next week I’ll find out if his successor will be as caring and accessible going forward. Moving forward into an uncertain future is scary on so many levels for most parents of children with developmental disabilities. And, in this age of instant communication and social media, our fears are informed everyday by not only our current problems and our memories of past hurdles and injustices, but by our constant connection to the experiences of others. Today’s advanced ability to connect and share information has become a vital resource for parents, but it also provides a seemingly endless inventory of all that can and does go wrong in our children’s lives—abuse, neglect, inadequacy of supports, and the decline of once stable lives. For every one positive story there are ten that rip your heart out. I know that although I am exhausted by this never-ending battle, I have no choice but to continue to compel others to care whenever I can. But, there shouldn’t have to be advocacy to gain rights and respect for people who should never have been without them in the first place. I look at my Lauren who has lived with grace and simple acceptance of overwhelming challenges for all of her thirty-three years and I wonder, Who can deny that she is worthy of their admiration and best efforts to assure that her life is not further wounded by their actions.....or inactions? But the voices of advocates are all too often not much more than a whisper amongst the clamor of the many issues competing for the attention of people who hold our fate in their hands. Our president has just submitted a budget that includes deep cuts to Medicare and Medicaid – the primary funding source for disability services and supports. Over a decade, President Trump’s plan would reduce Medicare by over $800 billion and cut Medicaid spending by $200 billion. The plan also calls for cutting programs such as independent living programs, respite care, and state councils on developmental disabilities. It would seriously cut funding for Special Olympics and do away with a $51 million initiative to address the needs of those with developmental disabilities and autism. Opponents of his plan say these cuts are being used to make up for the revenue shortfalls created by corporate and individual tax cuts passed in 2017. Individuals with developmental disabilities and their families can only hope that someone in Washington will be compelled to care that they do not become collateral damage. And like all too many other things.......Isn’t that sad?  Every single time my cell phone rings, my heart starts to thud in my chest. It feels like it’s trying to escape the muscle and bone that contain it. Slightly light-headed, I can’t grab the phone fast enough to see the caller ID, often fumbling with the wrong side up, upside down phone in my haste to read the screen. A mantra runs through my brain, Let it not be them, let it not be them, “them” being whoever is caring for my daughter at that moment. My ding-dong text alert results in the same response. Crazy thing is, this happens even if I’m with Lauren—my body’s learned response akin to Pavlov’s dog. It’s the result of too many years of a ringing phone being a call to arms, or rather a call to run. And if not necessitating a mad dash out the door, at a minimum, the ring signals some problem or issue affecting Lauren’s well being. Lauren’s early years were such an uphill battle, so strewn with things for me to panic over, that panic has become my default response to even the potential of a problem. It’s probably some primitive, fight or flight response, helping me prepare for even the possibility that heightened preparedness is needed. And, it’s exhausting. In a recent post, when referring to parents raising children with severe developmental disabilities, I used the phrase, ”the post-traumatic stress of raising their child to the present day...”. Do parents actually develop post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD)? Can parents on this difficult journey suffer from something we more frequently associate with veterans of combat and military operations? Researchers are beginning to study the effects that raising a child with a life-threatening or serious and chronic conditions can have on parents. Studies have measured the cortisol levels of parents of children with disabilities and found them comparable to individuals who have been diagnosed with PTSD. Cortisol is a hormone that regulates many of the body’s processes including metabolism and immunity. These increased levels of cortisol put individuals at risk for compromised mental and physical health. It may result in fatigue, decreased immunity, mood disorders, poor sleep, headaches, gastrointestinal problems, and increased vulnerability to stroke, heart disease, and hypertension. The American Psychiatric Association defines PTSD as a psychiatric disorder that can occur in people who have experienced or witnessed a traumatic event, something that is generally outside the range of usual human experience. Most parents of children with developmental disabilities have had ample evidence over the years that their parenting experience is far from the norm. The clinical criteria for the diagnosis of PTSD is a lengthy list that explores the nature of the exposure, the presence of symptoms such as flashbacks, reactions to related events, and prolonged distress. It also looks at negative alterations to cognition and mood, symptoms such as hypervigilance, irritability, sleeplessness, and the duration of all of these symptoms. Everyone reacts differently to the “outside the range of usual human experience” experience of raising a child with developmental disabilities. And, no two experiences are exactly the same. Our children, their unique challenges, our families, our culture, our communities, its resources, and our own personal resources and challenges all contribute to our individual experience of raising a child with special needs. The development of PTSD in a parent depends on all of those interrelating factors. Reports and studies specifically about the occurrence and prevalence of PTSD in parent of children with disabilities are few, but growing. Researchers note that a single traumatic event or the ongoing condition of a child can cause PTSD. Data from sixteen pooled studies show the prevalence of PTSD in parents of children with disabilities at 23%. Another study shows the prevalence at 30% with another 30-40% experiencing symptoms significant enough to impair function. Because these studies include parents of children with all disabilities and medical conditions—not just developmental disabilities—the true prevalence specifically in that subgroup is unknown. Parents tend to develop an exclusive focus on their child’s life management and well-being—totally engaged in their child’s challenged experience of life. An interesting survey by anthropologist David Marlowe has shown that witnessing harm to, or the distress of, others is actually more traumatic to an individual than experiencing danger or trauma themselves. Parents do not make their own well being a priority, nor is it the priority of professionals caring for the child. In order to facilitate connections and solidarity among parents having similar experiences, parents, especially in the early days, are sometimes referred to support groups where they can share their experiences with each other. I had my own experience with a well-meaning group that was part of Lauren’s Early Intervention Program. I wrote about it in Special Needs, “There are a lot of tears and monologues of woe in this stuffy room, and the hands on the clock above the door, which is our only escape, move all too slowly. It is consistently painful to listen to the heartbreak of these mothers, of their dashed dreams and unrealistic hopes.” It’s been found that the sharing of similar experiences may actually add to a parent’s trauma by adding other’s experiences to their own, reinforcing trauma rather than providing positive reinforcement. When it comes to caring for and protecting your child— from an evolutionary perspective—it’s good to sleep lightly, wake quickly, react to strange noises and generally be vigilant. Anger keeps you ready to react; flashbacks are a reminder of potential threats. But this is usually a short term response, not a life-long need. It’s been said that in this type of survival mode, you don’t thrive. You simply endure. Fellow mom, advocate, and blogger, Hillary Savoie, has said, “If your child’s health status is unchanged for the duration of their life or your own, how do you reorient yourself to regular life while remaining in anticipation of the repeat of a traumatic event: The thing that is harming you is also helping you to protect your child.” I can’t help but believe that a contributing factor in parents developing PTSD is the fact that raising a child with developmental disabilities can be an intensely isolating experience—the child’s needs and challenges creating barriers to social connection and participation. In Sebastian Junger’s Tribes, a book on PTSD, he notes that “In humans, lack of social support has been found to be twice as reliable at predicting PTSD as the severity of the trauma itself.” He also notes that, “....one way to evaluate the health of a society might be to look at how quickly its soldiers recover, psychologically, from the experience of combat.” Perhaps we should look at the increasing evidence of the occurrence of PTSD in parents of children with developmental disability the same way. Of course, most parents are not experiencing traumatic events every day. There are family dinners, things to celebrate, and blissfully boring days. But, Junger further explains that the interweaving of trauma with positive experiences makes it difficult to separate the two. When this goes on long term it creates a more complex scenario than a traumatic event that is limited or isolated. And raising a child with developmental disabilities into adulthood is all too often a long-term series of traumatic events. I think if a diagnosis of PTSD becomes more prevalent in the lives of parents of children with developmental disabilities, they will have to adjust the name of the disorder. There is no “post” to the stress, trials, and fears of continuing to support our children through adulthood. Coping mechanisms for overcoming the effects of trauma will need to be adjusted for those who must continue to endure in a role where sustained threats and disturbing events never end. I’ve tried many coping mechanisms over the years, but the results are temporary, superficial, insufficient. My morning meditation is frequently interrupted by a text message from a DSP. I’ve even tried changing the ringtone on my phone to something bright and breezy, an audible reminder of the positive potential as well as the negative. It didn’t help. It brings to mind the phrase--putting lipstick on a pig.....I still knew what could be behind that ring. It is difficult to remember when anxiety became my default emotion, when constant vigilance became more a norm rather than a situational necessity. Having Lauren changed my life in a far greater way than just adding “Mom” to the roles I planned to have. I became “mother of a child with severe developmental disabilities” and it was far more than a new role. That reality colored every decision, event, and possibility in my life. It had the conflicting effect of both expanding my concept of who I was and who I thought I could be, and limiting the content of my days and opportunities in my future. But most of all, it changed my reaction to and perception of the world and my understanding of the dangers that lurked within it.....for my child, yes, but also for me, lest something render me incapable of caring for her. And perhaps most of all, it has resulted in unending vigilance and a disturbingly informed fear of what could easily happen next. Is that PTSD? I don't know. I do know that whatever you may call it, it will be with me until my thudding heart no longer continues to beat.  As I read a recent article by New Yorker staff writer, Carolyn Kormann, I couldn’t help myself from seeing a parallel between the threat the giant iceberg in her story represented, and the threat that the instabilities of the disability service system represents to families. In Climate Change and the Giant Iceberg Off Greenland’s Shore Ms. Korman writes, “For a week, an iceberg as colossal as it is fragile held everyone in suspense. It arrived like a gargantuan beast that you hope won’t notice you, at the fishing village of Innaarsuit, Greenland, about five hundred miles north of the Arctic Circle. The iceberg posed a mortal threat to the village population of about a hundred and seventy people.... If a big enough part of it sloughed off, in a process known as “calving,” it would cause a tsunami, immediately destroying the little settlement on whose shore it rested.” Like that iceberg, the current resources for supports for adults with developmental disabilities are not actually a cohesive whole. That iceberg may look like a solid block of ice, but like these resources, it is actually full of cracks and fissures always in jeopardy of breaking into the disparate pieces that comprise it. Yet it is a wondrous presence for those who live humbly in its shadow..... until a piece breaks away. The loss of any piece that completes the puzzle of living as an adult with developmental disabilities can erode the stability and quality of an individual’s life. It can become a “calving” in an individual’s personal iceberg. Under the new Medicaid-based system of services we’ve just rolled out in New Jersey, a viable adult life requires piecing together supports and resources from multiple sources. That is mostly because Medicaid-based funding cannot cover expenses related to housing, utilities, or food. The majority of adults with developmental disabilities are going to need some type of residential option beyond the family home at some point in their life.....for the rest of their life. Any model that requires a piecemeal answer to the obvious need for adult residential options is problematic for individuals, who for the most part, will not financially or intellectually be able to create an independent life for themselves. The necessity of cobbling together resources and supports to meet the comprehensive needs of adults with developmental disabilities means that there are inevitable inadequacies and vulnerabilities in creating long-term, stable adult living solutions. There are pros and cons to this new Medicaid-based system. Aligning with Medicaid rules allows access to Medicaid matching funds bringing much needed federal revenue into the state developmental disability service system. However, aligning services and supports with Medicaid’s medical-model of billing and coding has created issues. It has eliminated the flexibility providers used to have in budgeting with known lump-sum funding. And, the rates assigned to services, which were determined by a lengthy and intricate process, were eventually funded below the recommended rates. For individuals who are self-directing, the fact that in this system funding is applied to individuals, rather than to programs, increases flexibility by putting the choice of how their funds are utilized (within strict parameters) in their own hands. But, completing the adult living puzzle for someone like my daughter means utilizing eight different resources—with different rules and access points—in order for all of her needs to be met. This piecemeal system of care is a frightening scenario when trying to establish acceptable long-term care options for adult children. It doesn’t matter if that option is under a provider’s wing or a self-directed option. We see provider’s struggling to make ends meet under this new system. How can that not affect quality of care if resources are insufficient? For families that have set up creative adult living options using multiple resources, each piece of that complicated puzzle is subject to change and is shifting constantly. Each year since Lauren moved into her own home there have been changes to the amount of funding, or rules governing the funding, of almost every single one of her funding resources. Keeping her life intact requires a delicate dance of sorts, moving and swaying to seemingly inharmonious notes, trying to maintain the balance and flow and budget of a stable life. I understand the trepidation of watching a hulking iceberg float wondrously yet menacingly nearby. As I wrote in Special Needs, “...the life my daughter is living is growing increasingly precarious. The systems that she depends on are constantly changing, and there is no guarantee that the supports she has today will continue to be there for her tomorrow.” Families who count among them a loved one with developmental disabilities are caught up in the same worries as all families. We’re inundated with non-stop news of political, financial, and social issues affecting our world. We just have the worries about the present and future of particularly vulnerable children on top of all that. All of these issues have the potential to trickle down to affect the resources we have no choice but to depend on to support the beyond-our-means, lifelong needs of adults with developmental disabilities. All of these issues could result in detrimental changes in our children’s lives, our children who have diminished ability to weather serious changes, especially when we can no longer help them. Change is not always bad. And yes, we need to serve the developmentally disabled population more effectively and efficiently. But as I’ve watched non-stop change in this system for the last thirty years, it seems as if our children and our families often seem to be used as nonconsenting test subjects for experiments in formulating viable service systems. Service systems are tasked with serving individuals adequately and equitably. That’s a lot to ask of a system serving this incredibly diverse population .....maybe too much. New systems seem to lack the adaptability of the former ones, the strict parameters and guidelines curtailing the option of using common sense to meet uncommon need or of preventing the unraveling of a stable life simply to suit newly instated rules. And it seems that each time change descends upon us, it is not something to endure and recover from. No, it is simply a temporary alteration not a long-term solution. We here in NJ, like many other states, have just spent years converting to a Medicaid-based “fee-for-service” (FFS) system. This was a drastic change from the former system and it was a difficult transition. The overall impact of the change is still to be determined. Now, we learn that a senior advisor to Health and Human Services Secretary Alex Azar recently stated that one of the prime goals of his position is to “blow up fee-for-service”, that is, to get rid of the Medicaid FFS model. This means that more change is definitely coming........again. Feedback on the FFS systems across the country is in. A 2018 survey by the Kaiser Family Foundation in all fifty states noted that achieving value, quality and outcomes, “... means moving away from FFS (Fee-for-Service) payments.” A recent report by ANCOR (American Network of Community Options and Resources), indicates that a FFS system does not work and does not improve quality or value in critical systems of services and supports. The report states an imperative that new systems must do something that current ones are not “...promote continuity and stability for individuals, families, and providers.” Wouldn’t that be amazing? What is the alternative to FFS? The ANCOR report points out that ten “alternative payment models” utilized in eight states across the country are not resulting in an improvement on FFS. These alternative models, in various stages of implementation, are insufficiently tested, measure outcomes inconsistently, and few are achieving savings. In addition, they share the similar issues of FFS - inadequate payment rates, a lack of desperately needed investment in the direct support workforce, and a lack of utilization of stakeholder input. No matter how diligent, creative, or intrepid we are as parents, it just never seems to be enough to ensure the security of our children’s futures. A new system, a new rule, or a funding change can arrive, and destroy or threaten, the hard earned stability or quality of our child’s life. Like the climate change that spawned this behemoth of an iceberg in Greenland, families are subject to something over which we have little personal control. My child is dependent on publicly-funded systems today and for all of her tomorrows. The fact that those supports exist is something for which I am incredibly grateful. What on earth would I do without these resources? But that dependency on something so ephemeral in its constancy is incredibly worrying. What if someday Lauren’s simple but comfortable life unravels because someone, who has never even seen the long-lashed brown eyes of a woman in a small town in New Jersey, changes a program or cuts critical funding? What if I have succumbed to the inevitabilities of aging and infirmities, and I cannot protect her? The weight of that hangs over my days like a storm cloud threatening a sunny day. I know there are many people diligently working to formulate systems and supports that will work for people right now. But that is their job for today. We’ve seen administrations on all levels come and go, leaving their successes and failures behind with our children and families. What is missing is a commitment to a tenet attributed to the Hippocratic school of thought, “...help or do not harm.” A demonstrated commitment to that would provide tremendous relief for families worrying about the long-term well being of their children with developmental disabilities. But, we are not there yet. So, I cannot help but worry about Lauren’s future dependent on resources with a long history of instability. And like the villagers of Inaarsuit I know my worries are not unfounded. Last summer, a neighboring village, Nuugaatsiaq, was inundated by a three-hundred foot wave. Now, the villagers of Inaarsuit have ample evidence, as we who endeavor to ensure safe and stable futures for our children do, that there are no guarantees when living in the shadow of an iceberg. The Direct Support Workforce Crisis: An Added Challenge for People with Developmental Disabilities2/28/2019  Several times in the pages of Special Needs, I wrote about the Direct Support Professionals (DSPs) that support my daughter. They are as essential to her survival as the air she breathes and the water she drinks. I worry that the crisis in the DSP workforce is one of the most significant threats to Lauren’s current and future well being. No matter how much time, effort, or love I have put into raising Lauren, no matter how hard I have tried to follow the advice to give my child roots and wings, this child will never fly solo. She will be totally dependent on someone to support and guide her each and every minute of each and every day of her life. No matter where Lauren lives, she will be dependent on DSPs. If a stable workforce of DSPs, adequate in number and competency, are not available to support her for the rest of her life, she risks neglect, isolation, and other things that I can’t bear to put into words. It’s hard to really imagine the vulnerability and dependence of someone like Lauren. Think about your own life, the many decisions and details that make up your day, the things you can do for yourself that you take for granted, the choices you don’t even consciously make. What if you needed someone else to do, or help you do, all of those things? What if you couldn’t tell them what you need or what your preferences are? What if you were dependent on them showing up each day with a commitment to facilitating your very survival? What if the simple fact was, without them, you would die? Lauren’s DSPs are responsible for everything from getting her up each morning to tucking her into bed and then monitoring her well being throughout each night. Three DSPs cover three busy shifts each day.

Each day has specific routines for Lauren and her DSPs. Keeping a basic framework to her days makes it easier for Lauren to anticipate and understand the moments of her day. But no two days are exactly alike.

Throughout each day the DSP is required to follow protocols and keep records that are vital in order for the DSPs in all shifts to follow the progress of Lauren’s day, adjust her care as needed, and gain hints to the meaning of Lauren’s efforts to communicate.

Listing the tasks and supports performed by the DSPs does not really capture the more nuanced aspects of their job. Lauren is usually a quiet and smiling young woman content with her music, watching her fish swim in their tank, and with an occasional excursion to the mall or the park. But then there are the other days, the days that her lack of an ability to effectively communicate is especially trying for both Lauren and those trying to support her. Sometimes Lauren seems angry or irritable. She rocks in her chair. She utters loud and forceful vocalizations. Nothing seems to make her comfortable. Does something hurt? Is she just in a bad mood? What is she trying to say? This behavior often lasts for a day or two.....or more.....before she has a seizure. In a forum for people with seizures, I’ve read that some people feel something like static in their head or a tingling in their body. Some feel that the room feels like its shaking, or they have an extreme sense of dread. Some say they just feel weird. All of them console each other on how difficult it is to put into words how they feel. Imagine how difficult and frustrating it is for Lauren, and how difficult it is for the DSP to figure out how to support her through this time. The DSPs are also responsible for developing and facilitating social opportunities for Lauren and providing the emotional supports without which Lauren’s quality of life would drastically suffer. Lauren does not have many people regularly in her life who are not paid to be there. She depends on the DSPs to not only provide the basics of care; she depends on them to literally help make her life worth living. Because Lauren lives in her own home—an arrangement we’ve found most appropriate for addressing Lauren’s preferences and needs—her DSPs work in isolation, without the daily support of co-workers. Each one works independently with Lauren during their shift, but they approach their combined role in Lauren’s life as a team, supporting each other with regular communication and problem solving. The DSPs role in Lauren’s life encompasses a lot of responsibility, a lot of vigilance, a lot of patience, a lot of caring. Lauren has been able to successfully live in her own home for the last eight years because of the quality and stability of the DSPs that support her. Today, I can have peace of mind that Lauren is cared for by people with the skills and knowledge required. That’s an incredible thing for a mom who once could not imagine her child surviving without her daily care and oversight. Because of the caring DSPs that Lauren has in her life, she was able to transition to this independent life much easier than I transitioned to letting her go. As I wrote in Special Needs, “I have had a much harder transition than Lauren did. Her room divested of her treasures, assorted shoes lying about, and pictures of the people who have loved and cared for her, is simply a room. That room, which had been so full of Lauren’s constant noise, too many seizures, and the breezy voice of Kenny Chesney, is now simply a room…..an incredibly quiet room. In fact, the entire house has a stillness as if she took the energy of our home with her when she left.” She did indeed take that energy with her, and it is now being nurtured and supported by the DSPs that enable Lauren to live her best life in a home that she loves. But what about tomorrow? Three years ago, we had to replace a retiring DSP; it took six months to find someone. The crisis in the DSP workforce has worsened since then. Pay rates, providing DSPs with less than a living wage, are the primary reason for the lack of a sufficient workforce to provide necessary supports. Despite nationwide recognition of this crisis, there has not been the required investment in stabilizing this vital workforce. Why? Perhaps, as I noted in Special Needs, because “these caregivers are primarily women (a historically undervalued group), providing care (a historically undervalued job), for people with developmental disabilities (a historically undervalued segment of the population).” Each day until this crisis is addressed, Lauren’s well being is at risk. At risk not because of the difficulties of her many challenges, but because the sudden loss of a DSP could unravel her safe and stable life. It will, at a minimum, take months to replace a DSP, months in which Lauren cannot survive without care, or with a revolving door of temporary workers who will not know or understand her. During those early years of learning about the overwhelming challenges that would be Lauren’s lifelong companions, I never would have believed that we would have to add the lack of access to an adequate and competent direct support workforce to those challenges. I wouldn’t have believed it, because this is a challenge that does not need to exist. This challenge is not something Lauren must live with. This challenge has a solution, and is the only one in her life that anyone has the ability to spare her. |

Gail Frizzellis the author of Special Needs: A Daughter's Disability, A Mother's Mission. Gail is an accomplished advocate and writer in the field of developmental disabilities and Mom to Lauren, a young woman endeavoring to lead her best life despite severe challenges. Archives

September 2019

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed